FIRST AMBULATORY CARE CENTER IN THE U.S. TO PURSUE PASSIVE HOUSE

FIRST AMBULATORY CARE CENTER IN THE U.S. TO PURSUE PASSIVE HOUSE

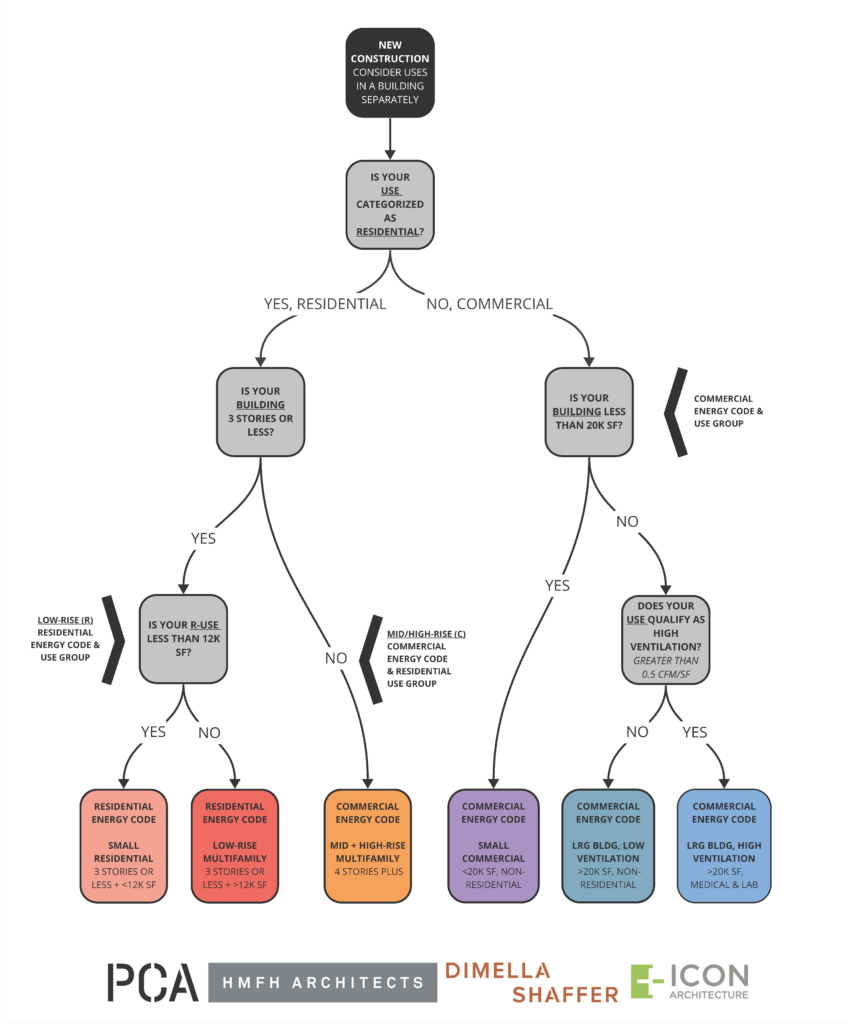

At DiMella Shaffer, our work spans a wide range of new and existing building types—from commercial and academic labs to multifamily housing, student housing and athletic facilities, senior living, and workplace environments, each of which is uniquely impacted by the evolving Massachusetts Stretch and Specialized Opt-in Energy Codes. To help our teams navigate this complex regulatory landscape, we’ve developed an energy code map and Decision Trees. Both tools are updated regularly and used at the outset of every project. These resources clarify compliance pathways based on building type, size, and ventilation requirements, helping us reduce carbon emissions from day one.

One standout example of this strategy is a new 4-story, 110,000 sf ambulatory care center in Quincy Center, now under construction. Quincy adopted the Stretch Code in 2011 but has not yet adopted the Specialized Opt-in Code. Because the project exceeds 20,000 square feet, it is considered a “large” commercial building.

Working with mechanical engineer WSP, our first step was to determine the building’s average ventilation at full occupancy. Despite certain zones requiring higher ventilation, the building’s overall average came in below 0.5 cfm/sf, qualifying it as a low-ventilation building. This opened the door to two compliance pathways: Passive House or TEDI (Thermal Energy Demand Intensity).

Five Key Lessons from Designing the Medical Office Building to Meet Passive House Performance

1. Choose your Path Early

When the project began in early 2023, TEDI was still a relatively new pathway. Our team chose the Passive House pathway, and collaborated with sustainability consultant Steven Winter Associates to guide both the core and shell and tenant fit-out. This decision makes the project the first medical office building in the U.S. to pursue passive house certification through Phius CORE 2021 (Passive House Institute U.S.).

See the new construction main decision tree below.

2. Right-Size Your Glazing

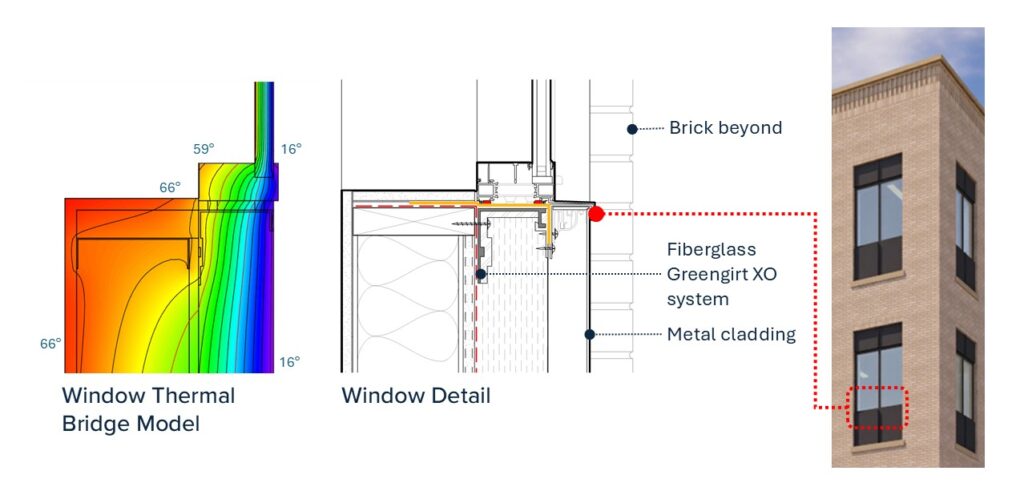

Windows are typically the weakest point in the building envelope. From the start, we planned for a balanced 20% window-to-wall ratio, prioritizing higher glazing ratios in public areas and replacing spandrel glass with insulated walls above and below each window.

This approach reinforces the façade visual openness while prioritizing thermal performance. Thermal breaks at window supports preserve the intended aesthetic, allowing the insulated walls to align more closely with the plane of the windows, ensuring continuous insulation across the envelope.

3. Minimize Heating Demand in Internal-Load Buildings

Medical office buildings are internal load dominated, meaning equipment, lighting, and occupants generate significant heat. This allowed us to meet passive house performance targets using double-pane windows and a high-performance envelope, rather than triple-pane windows.

In contrast, skin-load dominated buildings, such as single-family homes, rely heavily on the envelope to resist heat loss and gain, often requiring triple-pane windows.

Envelope attributes for this project include:

- U-0.24 double-pane windows

- R-24 insulated walls with minimal thermal bridging

- R-40 roof

- ≤ 0.08 cfm/sf airtightness

These strategies reduced the projected heating demand to just 3.25 kBtu/sf/yr—less than half the Phius limit and aligned with the 2023 Stretch Code’s goal of reducing carbon emissions and grid strain during cold weather.

4. Meet the Source Energy Limit

Phius sets a source energy limit of 24.5 kBtu/sf/yr for commercial buildings, accounting for both site energy (energy use within the building) and losses from power generation and transmission.

Medical office buildings often exceed this due to high “process loads” from equipment like MRI machines and specialized spaces such as the compounding pharmacy, which has specific ventilation needs. Fortunately, Phius allows adjusted targets for both cases, raising our limit to 55.7 kBtu/sf/yr.

Strategies to meet the source energy limit include:

- All-electric heat pump systems for heating, cooling, and hot water

- Energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) with 87% efficiency

- On-site solar panels to offset plug loads

- Swegon React Dampers to reduce ventilation by 50% during unoccupied hours

5. Leverage Available Incentives

High-performance buildings can benefit from generous state incentives. This project is on track to qualify for Mass Save Commercial Path 1, with anticipated incentives including:

- Up to $2.00/sf at project completion

- Up to $1.50/sf one year post-occupancy

- $1,200/ton for the selected variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system

These incentives help offset upfront costs while delivering long-term operational savings.

A New Standard for Medical Office Buildings

Under the previous Stretch Code, this building would have only needed to exceed ASHRAE 90.1-2013 by 10%. Transitioning from ASHRAE to passive house may seem daunting, but with early planning and a shift in methodology, it’s both achievable and cost-effective.

The result? A net-zero ready ambulatory care center that reduces environmental impact, lowers operating costs, and sets a new precedent for healthcare facilities across the country, reflecting DiMella Shaffer’s commitment to sustainable, forward-thinking design.

Very happy to see a large building pursuing passive house standard in Quincy. Thank for describing the decision process, and for outlining the benefits, feasibility and cost effectiveness. Hopefully there will be only be low or net zero emissions buildings in our community considered for new construction soon.

Is there a total project and/or construction budget for this project?

Thank you for your question. At this point, the budget for the project is confidential per the request of our client.

Any updates on this project!? I’d love to hear!

The project is in the early stages of construction. The topping off ceremony was last week.